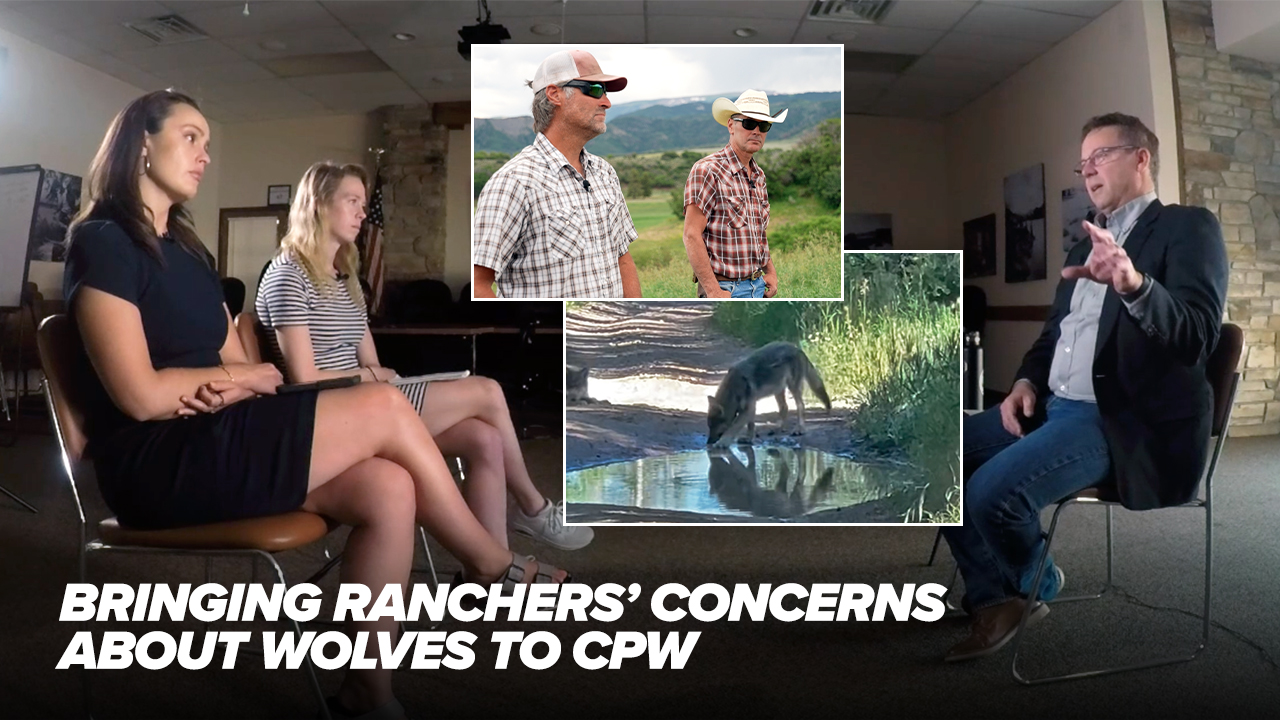

DENVER — After spending an afternoon with two Pitkin County ranchers whose cattle have been impacted by a nearby wolf pack, Denver7 sat down with the leader of Colorado Parks and Wildlife (CPW) to bring their concerns to him.

Early last month, Denver7's Colette Bordelon and Stephanie Butzer visited Michael Cerveny and Brad Day to see how their operations in Pitkin County have been negatively impacted by the controversial re-release of the Copper Creek Pack, which has a history of livestock depredations. The pack is made up of two adults, four yearlings and an unknown number of pups.

A few days later on July 7, we reached out to CPW to set up an interview with CPW Director Jeff Davis, ready with about a dozen questions from both the ranchers and our own research. That same day, we contacted Gov. Jared Polis' office requesting an interview as well.

Denver7 sat down with Davis on Thursday and our full interview is below. We touched on various topics surrounding livestock producers and this wolf pack, including transparency within the agency, the level of Gov. Jared Polis' involvement in the program, efforts to pause future releases, and the single problem animal within the Copper Creek Pack.

The Copper Creek Pack was re-released in Pitkin County in January after being captured last year following a string of livestock kills in Grand County. CPW has confirmed seven cases of wolves depredating — meaning killing or seriously injuring — on livestock in the county this year, as recently as June 18.

Cerveny and Day said they know their chosen careers come with a slew of challenges, but their concern about wolves specifically stems from this pack, and when the issues surrounding those animals will come to a close.

Local

Pitkin Co. ranchers question why wolf pack was re-released near their cows

“You really feel how small you are in this big machine of politics, and how you just truly are this little speck in this whole process, and these people don't seem to care one bit,” Cerveny said.

The same day that Denver7 published that story, we learned via a letter from CPW to the Holy Cross Cattlemen’s Association that CPW had agreed that killing another wolf in the pack was appropriate. That effort is ongoing.

- Hear from the Pitkin County ranchers about their cattle, the re-release of the Copper Creek wolves nearby, and what questions they have for CPW in our in-depth report here or below.

Earlier this summer, Director Davis visited the ranchers to hear directly from them. But the men told Denver7 some of their questions remain unanswered.

"I'll stick with my original question that I had for Jeff Davis: Who decided that this Copper Creek wolf pack was to be dropped off where there's a lot of cows in the middle of the winter? We've yet to be answered that question," Day told Denver7 in early July.

They wondered about any plans to capture and re-locate the pack again, or move them to a sanctuary, as alternatives. The men noted the wolf management plan reads that "The translocation of depredating wolves to a different part of the state will not be considered, as this is viewed as translocating the problem along with the wolves," and felt that the pack's re-release in January directly contradicts this.

The ranchers also questioned if Gov. Jared Polis is the "ultimate decision maker" when it comes to wolf management in Colorado, and if Davis has the authority to listen to and act upon what his district wildlife managers (DWMs) across the state are reporting back to him — or if somebody higher up, like Polis, has too much control in those decisions.

"We're being told that they (DWMs) support us," Cerveny said. "They know what we're going through is wrong. They know that this pack should be removed, but at the end of the day, they're telling us that Jared, that Gov. Polis, is making that decision."

Denver7 brought these questions and more to Director Davis for a 30-minute sitdown interview on Thursday at CPW Headquarters in Denver.

The below Q&A has minor edits for clarity, but contains the full interview.

Q. Tell me a little bit about your background. How long have you had that position? What did you do before this? What qualified you for this?

Yeah, so not sure about the qualification (laughs). I've been a public servant for over 26 years now, most of that time was spent at the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife in the director's office, working on habitat and conservation policy issues. I've had this position for over two years, although I arguably age in dog years, or wolf years, so I feel like I've been here about 700 years.

Q. We’re going to start with general overviews. Quick overview of the wolves. How many are in Colorado? How many have died so far?

I don't keep that kind of daily total in mind, because these animals… We know there are, for example, reported three uncollared animals that have come into Colorado. We have the pups that, more recently, we know there's at least six in one pack and three in another, with video and photographic evidence of those. But also — it's the wild. Nature is not a Disney movie. We do know that on average in the western states, pup mortality is 40% to 50%, so we really focus on a total minimum count annually, and that will be in our wolf updates reports.

We've released — relocated — 25. So, we're still short of what the plan calls for: 30 to 50 relocations. Those are going to be really critical.

- Read the full Colorado Wolf Restoration and Management Plan

I know there's elevated pressure to stop releases, but those are really critical from a genetic perspective — that we have somewhere in that range of 30 to 50. Today, I couldn't tell you (the total), because I don't know if another wolf wandered in from Wyoming, and we've had wolves leave Colorado for a short period of time and come back, or leave and suffer some mortalities.

Reporter's note: As of publishing time, seven wolves have died in Colorado in 2025. Denver7 is tracking the known number of wolves in the state, and you can find those details at the bottom of this story.

Q. A lot of the ranchers we've spoken with believe there's a lot of secrecy around the wolf reintroduction program. Would you agree with that assessment?

When it comes to my favorite word, "transparency," I think that means different things to a whole lot of different people. We have to keep these animals and their locations safe, and I think that kind of feeds into “Are we being transparent?”

I also feel like there's a perception that we know where every single one of these animals is at any point in time. The technology just has us knowing afterward. Because these capture data points, location points, but then they're uploaded some period of time after they are in those spots.

And then just standardizing our communication with producers, I think, is going to be a continuing effort for us, because some producers are fine just with, “Hey, nothing's really happening,” or, “Hey, we have new wolf activity in the area” and others may expect a daily call. And again, being mindful of, if we talk about the Pitkin area in particular, we're on record-high bear calls too. And so, our folks are doing the best they can with making sure that we're staying in touch with the local producers on the wolf activity.

I think the transparency also comes into play from the advocates that fought hard in order to ensure that we had this law and this program to restore wolves to Colorado. They want to know more about what's going on as well, and we're doing the best we can in learning what are the expectations and what can we actually deliver on, versus what the technology may not allow us to do.

Q. Looking at the wolf reintroduction program as a whole, what would you say is working and what is not working?

I think CPW plays a role, obviously, as the public trust manager in this situation, and the wildlife experts in the state. So, the biological pieces are the easy parts. It's the social pieces, right, that you're writing about a lot. We experience (that) on a daily basis, in some cases hourly — just helping the social evolution that always comes with wolves. And that's externally, with the producers and the advocates and the general public, which you guys play a tremendous role in helping us with that social evolution and in these types of opportunities we have together.

There's also internal evolution that's happening too, right? We have a lot of our staff, biologists, officers, that are part of these communities, that are evolving as well. So, I think (there’s) a lot of focus on the social evolution, and what can we do to help people be more comfortable as we evolve in this together and recognize these are wild animals too. And so, I think that's part of some of that transparency of “They said one thing one day, and they're saying a different thing a different day.” Well, these are wolves, and they're wild, and that's part of this restoration effort. And we can't always predict with 100% certainty what's going to be the situation tomorrow. I think the social piece is really a big focus.

There's another one that is concerning: the efforts to kind of stop releases. We're not at the 30 to 50 relocations, and the genetic component of that is concerning.

Q. If you were to assign a grade to it, what would you give the wolf program today?

I would say probably a B. We will always have things we need to learn and adapt to. And you can look across the western states, and every one of them has different social, political dynamics. That's the case here in Colorado, for sure. I feel like on the biological side, we're doing a ton of research that I think will pay dividends for us and everyone that might be managing wolves in the country. Game herd research is going to be really important, because I know that's a lot of pressure, both on our hunting community that's very important to Colorado's heritage and economics, but also, it's a two-fold thing for the producers. Many producers also do outfitting, guiding. It's not just the livestock concern. It's also: What is the wolf restoration doing to the ungulate populations here?

And then the social piece is the social piece. You know, there's differences in Colorado of elevations, for example. And so when I think biologically, if we have a pack set up or a den site that's down low, and then our ungulate populations move up early, for example, that puts a lot more pressure on the range rider program and non-lethals to make sure that we don't see an increase in livestock-wolf conflicts, until such time the wolves can move up and follow those deer and elk herds.

Q. I want to get into the wolf reintroduction plan, and specifically that one portion that says that CPW will not move depredating wolves because they see it as moving a problem along with the wolves. Why go back on that plan when it comes to the Copper Creek Pack?

A not-very-visible or well-understood component, unless you're in the process of developing the plan, (is that) it calls for a lot of adaptive management. Could we have foreseen that in the first year of relocations, that we would have a breeding pair in that location in that situation? No. No one could have predicted that. At the same time, we have, as the law says, (to) develop a sustainable population of wolves and resolve conflicts with livestock. And so, in that particular space — I've said it publicly — it was a perfect storm. Did the producers think at all about, or know, the dead pits would be an attractant? In my experience with those folks, they weren't thinking about that, right? And so, it's things like that.

Today, we're in a way better spot with a really effective range rider program. Do we need to grow that? Yes. Non-lethals, producers doing an amazing job, working with us to develop site assessments. We're just in a way different space. And at that time, it's our first breeding pack — successfully breeding pack. We have to build a sustainable population. And so, removing those animals would have been counter to giving, essentially, the female and the pups a second chance to contribute to that population growth.

Q. Do you believe that it did shatter some trust with producers?

I do. I listened to our internal experts, other agencies with expertise in this space, and think about: Would I do that relocation again? No. What my commitment publicly was is this is unique, and we're adapting to the unique situation we're in, giving these animals a second chance to contribute to the restoration program. And my commitment also was that we would collar all of those original pack members, and if and when they got into trouble, we would have a definition for chronic depredation, and we would take actions like we have.

The other thing I'm mindful of is there's a spectrum in all of this, right? There's producers that have very strong feelings about not wanting wolves in Colorado. There's a whole lot of producers that are like, “Yeah, I may not have voted for this, but they're here, and so let's work together to avoid and minimize those conflicts.” Similar, on the other side with the advocates — there's some that believe no wolf should ever be harmed in the making of a movie called humans, and there's a whole lot of advocates that are being very constructive in this space around how do we help the producers? Because that's truly where you get to the word coexistence — where there's social acceptance for these animals on the landscape, and ranchers can have some certainty that we're going to take care of them, so they also stay on the landscape.

And in my world, it's not just right now — I think they're just surviving. And not just from wolves. These folks are under a lot of pressures and uncertainties, right, that they have to navigate every year, every month. So, how do we help through this, potentially, and this is a dream world, maybe, but how do we get them to thrive in this space?

Q. How many wolves is CPW looking to lethally remove right now? We obtained a letter from the Holy Cross Cattlemen’s Association, saying that lethal means will likely be taken against the Copper Creek Pack again. And then with the chronic depredation out in Rio Blanco County, I'm wondering how many wolves are being hunted by CPW? And why isn't it made more public when those efforts go on?

Great questions. I am constantly hearing Copper Creek Pack is a chronically depredating pack. There's some circumstances that are slim where a whole pack is chronically depredating. That's not always the case. It's not usually the case, right? You have individual animals in a social pack structure that play roles. So, I say that to you for context, in that there's one particular animal in the Copper Creek Pack that we know has been involved in some of the early depredations, but also continues to show up within some of the allotments that the livestock are on right now, right? So we're targeting one specific animal in that space.

- The below video provided to Denver7 shows two wolves harassing livestock in Pitkin County on June 23, 2025.

Western wolf management is that when you have these situations, you take incremental steps to alter the behavior of the pack away from livestock interactions, and so that's what we're doing there.

In Rio Blanco, the (Lee) Fire is really driving… These communities are under a ton of pressure, a lot of uncertainty. They've got a lot of livestock, whether they're in the woods or on their ranches, right, that they're concerned about. How do I get my animals to safety in this situation? The fire is still relatively unpredictable in those communities, and, as I mentioned earlier, our staff are part of these communities, right? And so, they're also being evacuated, and having to deal with those evacuations of their personal residence. We're evacuating the Meeker office as we speak, and so our staff are also moving around. At the same time, we are (in) law enforcement capacity. And so, we're looking at, how can we provide eight to 10 officers to support the traffic and traffic control and evacuation support for those communities? And that has to, in my opinion, be our top priority right now.

Now, that animal still met our chronic depredation definition, and so what we're juggling is what is the current situation with the fire. We've got to keep staff safe in those spaces. And we also know that our staff getting out of harm's way, but also supporting others in those communities getting out of harm's way, has got to be our top priority.

Reporter' note: Three depredations have been confirmed in Rio Blanco County on July 20, 22 and Aug. 2. As outlined in CPW’s “Wolf-Livestock Conflict Minimization Program,” three depredations within 30 days is grounds for identifying the animal as a chronic depredator and therefore, CPW can lethally remove it. Denver7 reported on this on Tuesday.

Q. And why not publicize the lethal actions against the wolves?

So, in that space, that is standard practice, and I say that because that's for the safety of the animals and the safety of the operation and the safety of our staff. These animals — you get a very visceral reaction: Kill them and don't kill them. And some folks really value wolves, and they're very charismatic critters, despite how people might characterize them in “Little Red Riding Hood.” These are pretty amazing animals on the landscape. And folks really, on the other end, value them sometimes (as) equal to human life, right? And so, this is the balance that we play.

And because of those reactions, if you signal early that you're doing that (lethally removing a wolf), you can see interference. You can see threats coming in to staff, to myself, to producers. So, it's really important that we're able to conduct the operation and then share with the public — like we did in that initial Copper Creek Pack removal — “Here's all the factors that went into the decision that we made.”

Q. And looking at the Copper Creek Pack, we know that they were re-released in Pitkin County. How was that site chosen and was there knowledge ahead of time that there were livestock in close proximity?

Early in our analysis of planning for releases or release locations, we go through particular criteria: What are the game populations? Where will the game be upon that release window? What are the livestock operations in the area? And all those factors go into: Where can we, as safely as possible, release these animals and expect the least amount of conflict with livestock?

And that played out here in this process too. I know there's a lot of questions about transparency around the release of the Copper Creek Pack. I felt like we were pretty public that those animals were going back out. Part of the calculus in going south of Interstate 70 was to make sure that we didn't have her just take those pups and run right back to Middle Park and recreate a situation there.

Another piece I've heard is, you know, the producers there, that are being impacted, felt like we just dumped them there. This, again, is one of those lessons learned — adaptive management pieces — where all the other wolves we've released have gone some distance from the release location. For some reason, these went just a little distance and settled. And we did not anticipate that at all.

We have collars on all of these animals, minus the new pups that we expect in the pack. So, we are tracking these animals on a regular basis and making sure that when we have that livestock-wolf conflict, we're trying to identify the appropriate individual and take necessary actions.

Q. So, CPW did know there were cattle near the release site?

Yes. I mean, that is part of the criteria (as explained in the question above). We're trying to select locations that have the least amount of likelihood for cattle conflict, livestock conflict.

Q. We met with two of those Pitkin County ranchers who are experiencing some of these confirmed depredations, and they were telling us that you went out to visit a month or so ago as well. Can you tell us a little bit about that visit?

Like, you always question your life choices. My life choice was to be a public servant. And the saying, “If everyone's mad at you, you're probably in the right space,” comes to fruition almost hourly for me. But it's super important to me, in this space, especially with this particular pack, that I actually sat down with these folks and got an understanding of who they are. What's going on from their perspective? What solutions do they see moving forward? Because I think when we're people with each other, that's the best pathway forward.

I see a whole lot of “othering” happening here. It's producers or wolves, and I live in a public service space where it is “and" (meaning both). And it tears us apart at CPW, when we serve the whole public, to have the public essentially warring against one another and creating perceptions that dehumanize. So, it's important to me in this particular meeting to be personal and get to know them as people, and I've said publicly, these producers and their families are pretty darn amazing folks, right? And they're the type of folks that all Coloradans should want to keep on the landscape moving forward.

Q. They had concerns, even after meeting with you, about other members of CPW staff telling them in passing that the decision on what to do with the wolves really lies with Gov. Jared Polis, and not with CPW. What role does Polis play in this program?

This one's an easy one for me, right? The governor is our chief executive of the state of Colorado, right? I'm a division within the executive branch. And so, I brief the governor on all sorts of things that CPW is doing. The governor is a really intelligent human and asks really good questions, right? But that's the level of involvement. He said it publicly, and I've experienced it internally — he relies on CPW and our expertise to make the best decisions we can make moving forward. So yeah, he's not saying, “Do this, do that, don't do this.”

Q. Do you believe all the non-lethal tools are fully operating and fully funded?

I do believe that. And the caveat I'll put there is, as we expand the population and another round of animals, it's going to be really important that we expand, in particular, the human presence tool of range riding. And so, we're very focused on that. Lots of questions about, “Aren't you over budget?” The answer is no. The advocates have really done a pretty amazing job with our wolf (license) plate in particular, and so I think we're almost up to a $1 million in that revenue for those non-lethal programs.

So, this was anticipated that we would need to start with the appropriate capacity and tools. And recognizing that we'll have to expand those as the wolf population expands.

Q. One of the concerns expressed by Pitkin County producers is: “We're not asking for the Copper Creek Pack to be killed. But why not move them again?”

Why not replicate the thing I'm being attacked for?

Q. Or move them, they suggested, into some kind of captivity, potentially?

This is just my personal opinion: You're taking a wide-ranging animal and putting them in captivity. I think that's a worse sentence than lethal removal. There's been studies — I know Wolf Haven in Washington State used to take in wolves from the wild. They had two. One of those did not turn out well at all, and — my understanding is — they changed their policies to no longer accept wolves from the wild.

They also can suffer from PTSD. And in that particular case, as I understand it, because that animal had been captured by a helicopter twice, any time a plane or a helicopter flew over, there was submissive behavior and essentially signs of PTSD, right? So, putting them in captivity is an easy solution. It also would go back to the sustainable population of wolves. Here's my concern: We've had some mortalities. Those are anticipated. Most of those are natural. We have very strong efforts right now to block any future releases. Some people say pause, but that really, when is that “unpause” going to happen and who triggers that?

I'm concerned to just take a whole pack that seems to be productive — and again, they're not all chronic depredators — and put them in permanent captivity or lethally remove them… (That) puts us in a space where we're not growing a population and there could be some potential challenges to operations like that.

Q. Do you believe the yearlings would have learned from the primarily depredating wolf? Is that something that gets passed down to the younger wolves within that pack?

I would say that there's always that possibility. But again, I'll go back to — we had three yearling males and a yearling female. And I would say we have one yearling male that has been in and around livestock more frequently than all the others, right? And so, if the theory is, they see mom hunting sheep, then they'll all hunt sheep. That's just not playing out in the data that we can see.

Q. Do you believe the reported number of wolf depredations in Colorado is accurate with how many wolf depredations there have actually been on livestock?

I think this is why we have the “missing livestock” as part of our compensation program, because the livestock go into Forest Service (land), and in some cases, in the wilderness, and they're kind of out of sight and out of mind, right? We also, in the Pitkin area in particular, if you look at that country right now, it's really steep. It's dark timber with deadfall throughout it. Earlier on, scrub oak everywhere. So, it's not easy to see all the potential depredations that are out there. I would anticipate the ones that we're notified of and investigate is probably a smaller number than some of the impacts we see when they're out of sight, out of mind.

Reporter's note: Livestock producers can receive compensation for both killed and missing livestock. This exact equation is outlined in the management plan. Denver7 has reported on this type of compensation in this March 2025 story and this July 2025 story.

Q. The secret recording that was first published by The Coloradoan — it depicts a CPW employee talking about how she cannot confirm that a livestock depredation was from wolves. Is there any kind of reasoning or incentive for CPW employees to rule it's inconclusive versus conclusive, since there's obviously money that goes along with a wolf depredation?

Not to my knowledge. We're looking into that. And when I say looking into it — not looking into that particular employee, she's a rock star. She's doing a great job in that space. But if we have those pressures internally, I want to know about it because I do know there's a ton of pressure on our staff externally to call it a wolf, right? If you get to call it a wolf, then you (producers) get to have (file for) missing livestock. And I'm not saying producers are gaming that system, but there's a lot of pressure on our staff externally to call more of those wolves depredators, especially when it's in that “preponderance of evidence” space, right? Where it's not clear and convincing that a wolf did it.

And we got lions on the landscape. We got bears on the landscape, too. So, we have carnivores on the landscape that do depredate on livestock as well. The key, I think, is, how do we continue to allow our expert staff to follow the science and the evidence and give them the space to make the calls that they need to make, and we compensate for those losses, right? So, that's my hope. We're looking into some of those internal pressures, if they exist, and making sure that we give that space to our staff.

Q. We've heard from some ranchers that the compensation program's fair market price of livestock, which caps at $15,000, doesn't take into account the animal's genetics or future breeding. Does CPW feel like that $15,000 is still an appropriate amount of compensation for ranchers?

This is the key part: It's up to $15,000 right? And so, I wasn't around when the plan was being developed. (My) day two, plan got adopted, and Jeff was off to the races with this program implementation.

I know a lot of the livestock compensation — the values are much lower than $15,000. The $15,000 — my understanding is it was that because of that genetic lineage, right? And the value of that. Some of these folks have worked to create a very strong lineage, genetically, and the loss of those can be pretty significant to a herd.

Q. Is there anything you would like to say as closing thoughts?

(I’m) a public servant, right? I see every day, like, “My values are right and their values are wrong,” and as a public servant, it can tear us apart, quite frankly. And I just want to continue to push people: We've got to focus on the common ground, because there's a lot more common ground than areas of disagreement. When we can do that, this will go a lot better. I'm not just saying (for) wolves. I see this across a lot of the things that CPW has authorities over. It's just become more and more divisive.

We are people together — urban, rural. We depend on each other for our success in Colorado and individually. And so how can we remember that, and focus on that, instead of warring against each other over our differences?

Denver7 began reaching out to set up this interview with Director Davis, as well as Gov. Polis, on July 7.

A spokesperson for Polis was unable to set up an interview and sent a statement on July 24 about how Polis "did not advocate for, oppose or support the ballot measure" to reintroduce wolves.

Denver7 is continuing to work to arrange an interview on this topic with the governor.

Denver7 in-depth wolf coverage

The below list outlines an overview of the known wolf population in Colorado:

- Six wolves surviving from the original 10 that were released in December 2023 (one died of a likely mountain lion attack, a second died from injuries sustained prior to his capture as part of the Copper Creek Pack relocation effort, a third wolf became sickly and died, and a fourth - this story - died in Wyoming)

- Four of the five wolf pups born in the spring of 2024 (one male was killed after multiple depredations in Pitkin County)

- 10 wolves surviving from the 15 that were released in January 2025 (one was shot and killed by Wildlife Services in Wyoming earlier this month, a second died of unknown causes in Wyoming, a third died in Rocky Mountain National Park, a fourth died in northwest Colorado and the fifth also died in northwest Colorado)

- Unknown number of pups born in four packs in 2025

- Two wolves that moved south from Wyoming several years ago

- One uncollared wolf that was last known to be in northwest Moffat County in mid-February. It is not clear if it is alive or still in the state.

- Possible, but unconfirmed, wolf in the Browns Park area as of February. It is not clear if it is alive or still in the state.

Denver7 has been following Colorado's wolf reintroduction program since the very beginning, and you can explore all of that reporting in the timeline below. The timeline starts with our most recent story.