DENVER – “It’s like I exist, but I don’t exist,” Abigail Colón said.

Colón, a Colorado native, has spent most of her 30 years without a birth certificate — proof of identity the state said she can’t have because she doesn’t meet a little‑known documentation rule. Without it, Colón said she feels like a “ghost,” unable to get a driver’s license, health insurance or even legally marry her husband.

Her case, which is now headed to the Colorado Court of Appeals, could affect others across the state facing the same barrier.

To her family, it’s obvious she exists. Colón’s birth — recorded in a family Bible — lists Woodland Park, Colorado, as the place she was born. It’s one of the only records of who she is and where she came into the world.

When asked why she doesn’t have a birth certificate, Colón explained, “My father from a young age, because his parents are from Cuba… never trusted any form of government at all, and so he thought it would be in our best interest that we stay anonymous.”

Homeschooled and without a birth certificate, Colón cannot get an ID, health insurance or even a marriage license.

“It’s dumbfounding,” her husband, Eythan McKinnon, said.

Determined to fix the problem, McKinnon tried to obtain a delayed birth certificate from the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment (CDPHE). “No one was no one was answering me. No one would reach back out to me,” he said.

With their growing family came a growing sense of urgency, as she had difficulty with her daughter's birth certificate.

They contacted Colorado Legal Services and supervising attorney Casey Sherman.

“Abigail has been trying to resolve this since she was 16 years old. She’s just been getting requests for additional evidence, requests for additional evidence, until we stepped in,” Sherman said.

Court records show the evidence included everything from affidavits to a child protective services report from when Colón was 11 years old.

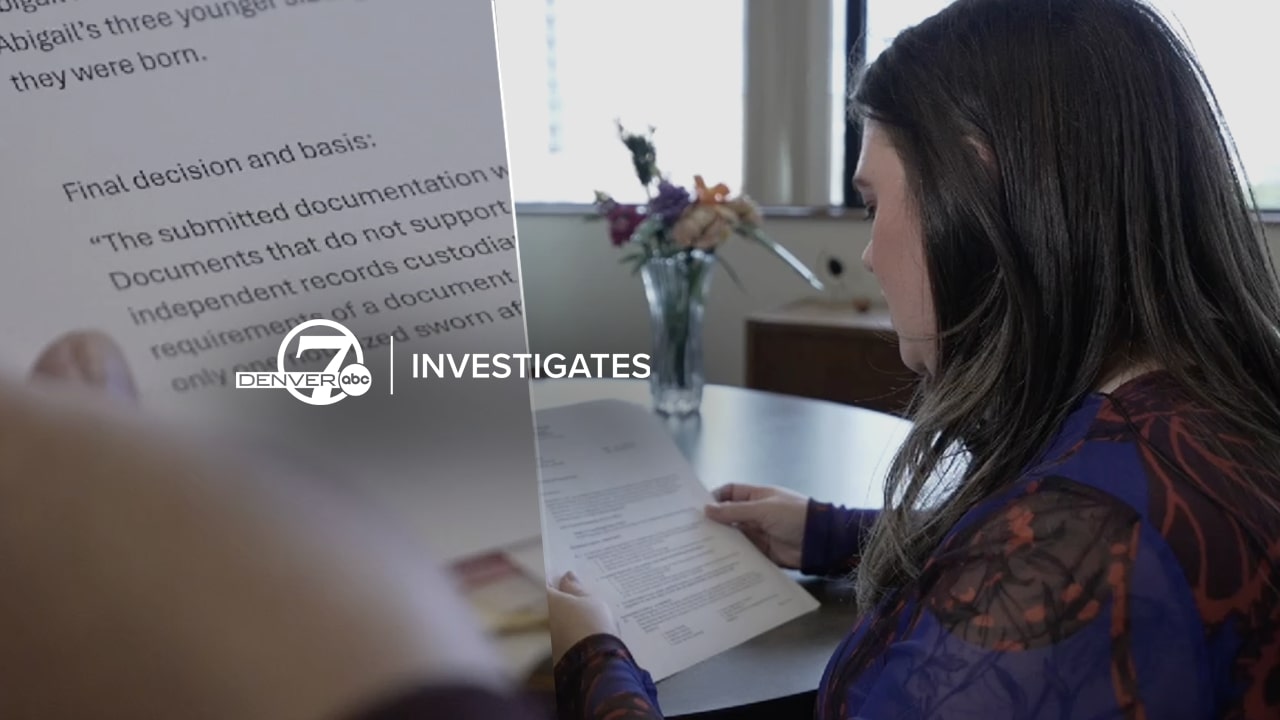

But the state ruled that the submitted documentation was insufficient and CDPHE denied the birth certificate application, citing no records from before Colón turned 10.

“She has to have a record before her 10th birthday, according to CDPHE regulations,” Sherman said, adding, “Colorado has the strictest delayed birth certificate law in the country without question.”

All three of Colón’s brothers have received birth certificates in Tennessee and Missouri, where judges can rule on such cases.

“They’re thriving, and I’m just here. That’s why I kind of feel like a ghost,” Colón said.

CDPHE told Denver7 Investigates in a statement that the rules are designed to prevent fraud. The agency added, “Privacy laws do not allow us to discuss an individual application for a delayed birth certificate.”

In the past six years, CDPHE has denied 84 of 347 delayed birth certificate applications — nearly a quarter of applications.

“I have five other clients that are waiting on the outcome of this litigation to hopefully be able to get their birth certificates too,” Sherman said. “The current law is unconstitutional and clearly unfair."

Now pregnant with her second child, Colón says she will keep fighting for her family and other unregistered Americans.

“I hope they find a little bit of compassion for those whose circumstances were out of their control when they were younger,” she said.

Colorado Legal Services and Colón sued CDPHE and lost in district court. They are appealing to the Colorado Court of Appeals, awaiting a court date.