DENVER — Over 20 measles cases have been confirmed in Colorado so far this year, more than the state recorded each year of the prior decade combined.

This week, the latest case was confirmed in a second Mesa County resident, who may have been exposed to the same person as the first, according to state health officials.

And last Tuesday, on Aug. 12, an infectious traveler who arrived at Denver International Airport may have exposed thousands to the virus as well, Denver health officials said.

The highly contagious and preventable disease has made countless headlines this year, with a total of 1,356 confirmed measles cases reported by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) as of Aug. 5. Thirty-two measles outbreaks have been reported to the CDC in 2025 as well, and the majority of confirmed cases are associated with those outbreaks.

For comparison, CDC data shows there were only 285 confirmed cases and 16 outbreaks of the disease in all of 2024.

A brief history of measles

Measles dates back to the 9th century, and became a nationally notifiable disease in the United States by 1912, according to the CDC. During the first decade of reporting the disease, an average of 6,000 measles cases were recorded every year.

By 1963, a vaccine for measles was available to the public but in the decade before that, the CDC estimates that three to four million people in the United States contracted measles each year, leading to hundreds of deaths and thousands of hospitalizations.

The vaccine, however, was not as effective as scientists had hoped and by 1968 a newer version was produced, which according to the CDC, is the only measles vaccine that has been used in the country since then.

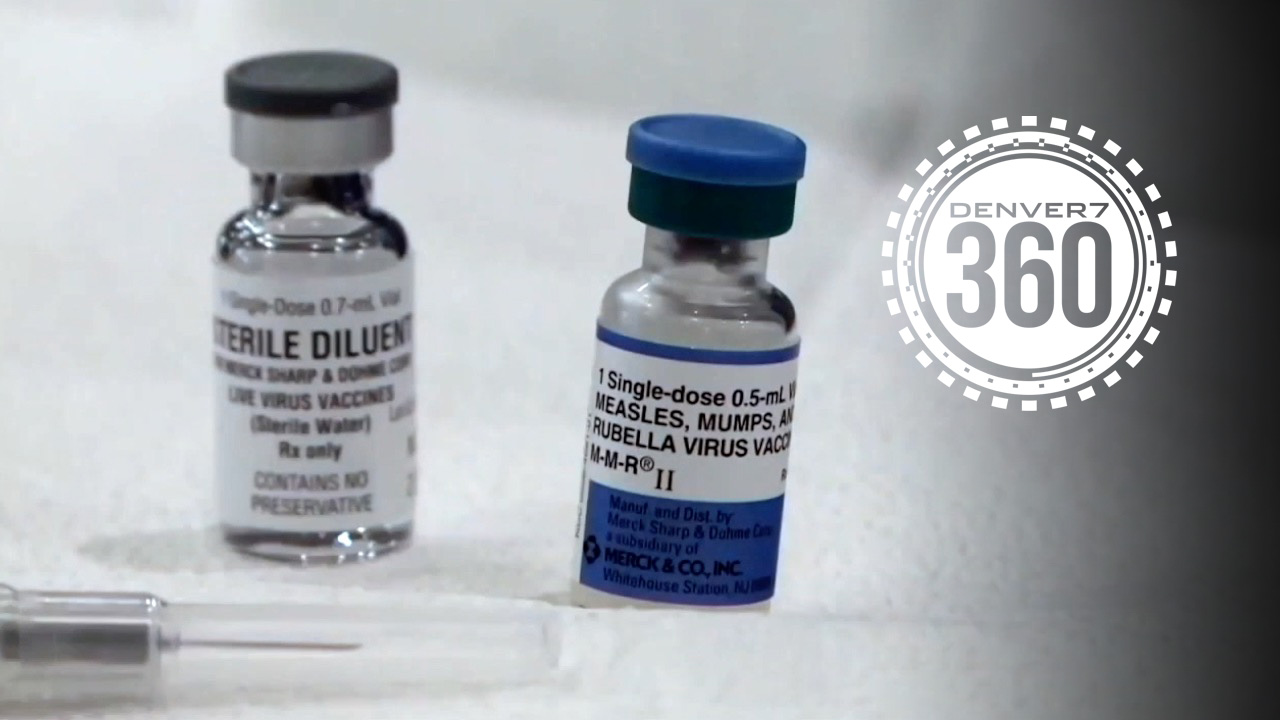

The measles vaccine, more commonly known as the MMR vaccine, is typically combined with two other viral infections (mumps and rubella) to help children mount an immune response should they encounter the virus as the grow older. There's also the MMRV vaccine, comprised of weakened versions of the aforementioned viruses, in addition to the varicella virus.

Historical data shows that in just three decades, the U.S. was able to eliminate the disease from the population, an accomplishment attributed in part to a "highly effective vaccination program," the CDC states.

- The graph below shows you how many cases of the highly transmissible virus have been reported each year since measles was eliminated in the U.S.

Measles in Colorado

Amid a multi-state outbreak of the virus earlier this year, health experts who spoke with Denver7 at the time said it was very likely Colorado would see cases of the disease start to pop up — especially in unvaccinated pockets of the state.

Those predictions came true about two weeks later, when Colorado reported its first measles case of the year since 2023 in an unvaccinated adult from Pueblo at the end of March.

Nearly five months since then, state data shows there have been at least 21 measles cases this year alone, four occurring in children under the age of 5 and the remaining 17 in adults. Ten of the measles cases in Colorado this year are connected to out-of-state travelers who flew while infectious, according to health officials, who also said out of the 21, 5 required hospitalization due to the severity of the disease.

Typically, Colorado only sees between one-to-two cases each year. Over a period of 10 years ending in 2024, the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment (CDPHE) saw only six cases of the disease.

"The biggest outbreak we've seen in the last 25 years"

Dr. Michelle Barron is the senior medical director of Infection Prevention at UCHealth. She told Denver7 that in the last five years, she has seen hesitancy around vaccines increase.

"This is the biggest outbreak we've seen in the last 25 years," Barron said. "We obviously have seen periodic cases, usually in people that have traveled abroad and then bring it back, but nothing like this."

One person infected with measles has the potential to transmit the disease to 17 other people, Barron said.

"It can stay in the air for up to two hours. You don't even have to be in the same space at the same time. You could have potentially been in the grocery line with somebody who has measles, who coughed or sneezed, and then two hours later you come in to check out, it's still in the air, potentially, and that's how you get infected," Barron explained.

- Denver7 has been closely following confirmed cases of measles in Colorado amid a multi-state outbreak of the virus in the U.S. this year. Explore the timeline map below to see more on where cases have so far popped up.

But Barron said there is a way to prevent illness — the MMR vaccine, which she touted as very safe and highly effective.

"Really there is no concern, from my end, in terms of offering this vaccine," Barron told Denver7. "One of the things that comes up is, 'Well, isn't it better just to have the infection?' And the answer, I would say, is no, because getting the infection means you are at risk of ending up in the hospital."

Data from the CDPHE shows 93.3% of Colorado students from preschool through high school received the MMR vaccine during the 2024-25 school year. That's almost a 2% decline compared to the 2020-21 school year, when 95.1% of Colorado students were vaccinated against measles.

"Anywhere where the vaccination rate is under 95% means that they're at potential risk" of becoming infected, Barron said.

That vaccination rate is the goal with the MMR vaccine, according to the state's top epidemiologist, Dr. Rachel Herlihy, who spoke to Denver7 about why that number is of particular importance.

"We know that's the herd immunity, or community immunity, threshold that will really prevent the virus from getting a hold here and causing an outbreak," Herlihy said. "Unfortunately, we've struggled for a while to achieve that 95% threshold, and that's certainly true right now where our vaccination rates are not as high as we would like them to be."

Data from CDPHE shows the majority of school districts across the state are beneath that 95% MMR vaccination threshold Dr. Herlihy would like to see for the 2024-25 school year.

Among those districts are Centennial School District R-1 at 86.6%, Colorado Springs School District 11 at 84.8%, and Moffat Consolidated School District 2 with the lowest MMR vaccination in the state, at 47.5%.

"Most concerning to us are these pockets of undervaccination that we see in certain communities where we see vaccination rates, you know, 80% or even lower in some places. And we know those are the communities in Colorado that are most vulnerable to measles outbreaks, potentially," said Herlihy. "What we are really hoping is that Coloradans that are not up to date on their MMR vaccine, or whose children are not up to date on their MMR vaccine, will see this as as an opportunity to become up to date, receive those vaccines, to ensure they are protected and that the Colorado community is protected from an outbreak."

Herlihy said typically, three or more cases of measles classify as an outbreak.

State health officials say two doses of the MMR vaccine can equip a person with 97% of protection against measles infection. Children are recommended to receive two doses of the vaccine, one between 12-15 months old, and the next dose before Kindergarten.

CDPHE reports that 72.3% of Coloradans, ranging from the ages of 1-18, have received two doses of the measles vaccine. For that same age range, 91.5% of Coloradans have received at least one dose of the vaccine.

How do holistic pediatricians view vaccines?

At Mindful Pediatrics in Boulder, Dr. Roy Steinbock blends together a traditional Western practice with natural medicine.

"At one point, I'd had probably like, 3,000 or 4,000 patients in my roster, which is pretty typical per doctor and doctor's office. But now it's much smaller. I mean, I probably average somewhere between six to 10 patients a day," Steinbock said. "The clientele that I have are generally very conscious. They're people who are super highly educated, typically, and are following what's going on the news. And of course, a lot of them are unvaccinated, so many of them are getting scared with the fact that there is a sort of uptick, or at least in the media, where there's a lot of attention towards the measles outbreak."

Steinbock said he has a conversation with patients almost daily regarding the MMR vaccine.

"The vaccinated patients are asking me if their kids are up to date. So you know, that's pretty easy to tell. And then, whether that's enough — are there other things they can do? Are there natural things that they can do?" Steinbock said. "The unvaccinated patients there, they've been trusting me, typically, for years. Or know of my reputation for being open-minded around vaccinations and kind of not as dogmatic as a one-size-fits all practice, and so they just want to know whether they think they should get the vaccine."

At Steinbock's practice, he is open to creating individualized vaccine plans for different families based on their specific needs. Still, as a general rule at the moment, he would recommend the measles vaccine for most people.

"It could spread like wildfire in a place where there's a relatively low vaccination rate. So I think overall, it's worthwhile, especially because measles is, it's not the common cold, it's a much more serious illness," Steinbock said. "It just needs to be personalized, and the timing can vary from child to child."

In the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic, Steinbock said he noticed a trend within his patients — he saw an increase in vaccinations.

"When COVID hit, that completely changed things. I had tons of families who obviously got very scared, and their kids had no other vaccines, but started vaccinating them for COVID, and then started catching people up. So, you know, interestingly, it was more, not less, over that time," Steinbock said about what he experienced.

Make America Healthy Again and vaccines

Denver7 asked Steinbock if he noticed any significant changes within his patients as the Make America Healthy Again (MAHA) movement grew throughout the country.

"It's not part of my conversation, because Boulder has always been like that. That's my clientele. Have I seen some people come in with Make America Healthy hats? Yes, but not a lot. It's mostly, just regular, typical, you know, lefty Boulderites," Steinbock said. "Those are definitely the people who seek out a holistic pediatrician."

To better understand the MAHA movement, Denver7 spoke with Ethan Augreen, who grew up in New Jersey and has lived in Colorado for roughly a decade.

"My personal health journey has been around nutrition and herbal medicine. And in 2020, I leaned more heavily into herbal medicine and nutrition, and I trust my body and knowing that I had the knowledge of antiviral herbs to be able to recover and heal if I did get sick," Augreen said.

Augreen said if not for the COVID-19 pandemic, he likely would not have vaccines "on his radar" in the way they are now.

"It wasn't really an issue that I was paying attention to, and I think that's true for lots of people. So certainly, the pandemic had a big impact on public health in this country and on people's attitudes towards the pharmaceutical industry and towards vaccine mandates and lockdowns," Augreen said.

During the 2024 election, Augreen was disappointed when Robert F. Kennedy Jr. — a vaccine skeptic who now leads the U.S. Department of Human Health and Services — suspended his presidential campaign. Augreen said he voted for now-President Donald Trump, trusting Kennedy's support of the Republican candidate at the time.

"I'm more of an Independent. I've voted for Libertarians in the past. I've voted for Green Party in the past. I have voted for Democrats in the past, too, but I always look the candidate on a personal, individual level," Augreen said. "Libertarian values, health, freedom values, transcend politics, and they're on all sides of the political spectrum. I think it's the establishment of the Democratic Party that has alienated those voters from voting for Democrats, but there are still many people who believe in natural health and health freedom, and they've had to move away from the establishment of the Democratic Party because they've come down so much for Big Pharma and for these vaccine mandates that are pretty totalitarian."

What role does social psychology play in vaccine hesitancy?

A study out of CU Boulder found that people who consume news from a number of different sources are more likely to be vaccinated, no matter their political affiliation.

"The study itself was primarily focused on COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy," said Dani Grant, the first author of the study and a PhD candidate at CU. "We were just curious to see if traditional news media impacted people's perceptions of vaccines, among other things like polarizing attitudes during the pandemic."

Grant, who studies social and political psychology, explained vaccine hesitancy and how it reaches across party lines.

"In the past, we definitely thought of it more as people who were left-leaning, farther left-leaning, were more inclined to be hesitant around traditional medicine and be more skeptical around vaccines generally," Grant said. "People now on the far-right are also leaning more into the holistic medicine, the kind of pure life philosophy that we would traditionally think of as like the far-left."

Before becoming a social psychologist, Grant would not have expected this kind of commonality between two opposite ends of the political spectrum.

"There's a lot of uncertainty in the United States right now and across the globe, there's a lot of things changing and a lot of threats going on, and we all, whether we're left-leaning or right-leaning, react in similar ways," Grant said. "We seek certainty. We try to make sense of the world around us. And in that sense, it doesn't surprise me, as a social psychologist, that because of this type of uncertainty that we're facing in our world today, that the far-left and the far-right would kind of converge on these types of issues."

Grant said in many scenarios, opinions on vaccines boil down to one underlying concern: The safety of one's children.

"There are people in in all of our lives that are skeptical about vaccines and lots of protective health behaviors that, you know, if we just started engaging with them more in productive ways and respectful ways, it really could change minds, and it takes time," Grant said.

Asking questions about vaccines

Barron, the expert on infection prevention at UCHealth, encouraged patients to ask questions about vaccines to their trusted health care providers.

"Again, all the vaccines are considered quite safe, quite effective, and most of it is the timing and making sure they don't interact with other vaccines," Barron said. "I'm happy that I live in a society where we can have these conversations. I think the problem is that people stopped listening to the full spectrum of things."

An open dialog between a patient and physician is what Barron believes is needed to make the right decision for any given individual.

"We will make the best decision with the information we have, and we will talk to you about it as well so that you can be part of that decision-making," Barron said.

Anyone who believes they may have been exposed to measles — especially those who have not been vaccinated with the MMR vaccine — should monitor for symptoms for 21 days and avoid public gatherings or high-risk settings, according to state health officials.

Symptoms to watch out for include anything from a fever, a cough, a runny nose, and red, watery eyes that develop into a rash that starts on the face and then spreads to the rest of the body about three to five days after symptoms first start. A person with measles is contagious four days before and four days after the rash appears.

Measles only spreads from people who show symptoms; it does not spread from people who aren’t feeling sick, state health officials report.

While most people recover within two or three weeks after contracting the virus, unvaccinated people run the risk of complications from the disease, including ear infections, seizures, pneumonia, immune amnesia, brain damage and ultimately, death.

Editor's Note: Denver7 360 | In-Depth explores multiple sides of the topics that matter most to Coloradans, bringing in different perspectives so you can make up your own mind about the issues. To comment on this or other 360 In-Depth stories, email us at 360@Denver7.com or use this form. See more 360 | In-Depth stories here.